Lena Waithe can’t help but write a little bit of herself into her characters.

“I can’t not. Yes, I’m the vessel, but because I am, some of me is going to get in there,” she told The New Yorker‘s Jelani Cobb earlier this month. “I do try and let the characters speak through me, but it’s also therapy for me. A place for me to work out my stuff. My favorite artists are the ones that you can see them in their work. You know what that person’s trauma is because it keeps popping up.”

That exploration of her own trauma through her characters has served the multi-hyphenate, who cut her teeth writing for shows like Bones and Nickelodeon’s How to Rock, well. It helped her become the first Black-American woman to win the Emmy for Outstanding Writing for a Comedy Series in 2017 for “Thanksgiving,” the highly personal season two episode of Netflix’s Master of None that was based on her own coming out experience. It helped land her a series order from Showtime for The Chi, a drama that brings to life her experience growing up on the South Side of Chicago that will return for a third season next year.

And it’s what’s rippling through every page of the script for Queen & Slim, her first feature film as screenwriter.

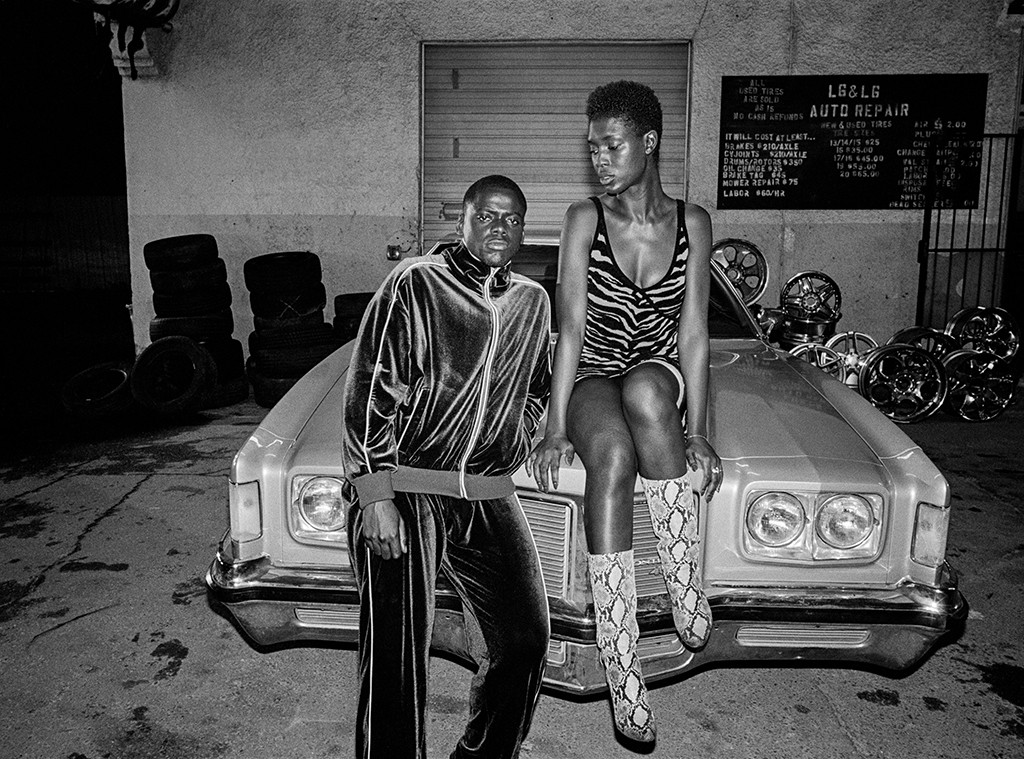

Inspired by disgraced A Million Little Pieces author James Frey, of all people, who approached Waithe at a party with an idea for a film he knew he had no business writing and retained a joint “Story By” credit for his trouble, Queen & Slim tells the story of a black man and woman who, after on a rather lackluster first date, get pulled over, wind up killing the cop in self-defense, and are forced into running for their lives. It’s a story that shines a spotlight on America’s grim racist past and present, directed with staggering beauty and urgency by Melina Matsoukas and starring Daniel Kaluuya and Jodie Turner-Smith, and one that’s been rather haphazardly been described as “the black Bonnie & Clyde,” a notion both writer and director are quick to dismiss.

“I think it’s a really simplistic and diminishing way to talk about our film,” Matsoukas told the L.A. Times in October. “I don’t really agree with basing black films on any white archetype. I think there’s a huge difference in who Queen and Slim are. They’re not criminals on the run, they’re two very human people who have a shared experience that was not their choice. I think that’s a very critical difference between them.”

MJ Photos/Shutterstock

For Waithe, the centering of the story on two dark-skinned Black-Americans was, itself, a revolutionary act. “It changes in every way because it instantly becomes political. It instantly becomes important. It instantly becomes revolutionary because of, literally, the color of their skin,” the newly-married scribe told The New Yorker. “And I think what’s so palpable about it is who they kill. And what do the police represent to us. They represent Jim Crow, injustice. They represent death to us, a lot of us. And for them to kill that in a complicated way. It’s not intentional, they didn’t go out and say, ‘Oh, let’s kill a cop tonight.’ They’re just existing in the world and trying to find joy and while doing that, they get pulled over and that joy is interrupted.”

While the story itself doesn’t necessarily draw from Waithe’s personal life, there’s an innate and inherent connection to the struggle at the center of the film, the struggle of just staying alive while black in America. It’s a struggle that, tragically, continued to repeatedly play out in the real world while Queen & Slim was coming to life.

“I had no idea this many more black bodies would’ve dropped by the time we got close to opening. I do not want that kind of publicity for the film. I do not,” she explained. “Because I am like every other black person. I am traumatized every time these stories come out. Every time these stories hit our phones, our Instagram feeds, our Twitter, our TVs, a piece of us dies because we know that we could be next. And I think that’s really where this story was born out of. Me feeling like a second-class citizen even if people feel like I sit in a place of privilege.”

It’s a project that might never have ever existed had Waithe’s experience as a new TV show creator not been as difficult as it proved to be. “I was sort of dismissed and told, ‘You’re no longer needed, we’ll take it from here,'” she told the L.A. Times last month. As she further explained to The New Yorker, “And that’s where I went and said, ”I’m gonna write something just on my own. That’s the thing no one can take from me.’ I just wanted to write something about us. But unfortunately, if I’m writing about us, how can I ignore the fact that we’re being hunted?”

Andre D. Wagner/Universal Pictures

Describing Queen & Slim as “protest art” and her contribution to “the culture,” Waithe told the L.A. Times, “I think for me, there’s no greater weapon than my laptop. I come from the church of Nina Simone, in that it is our job as artists to reflect the times. And by that, anything a black person writes is political. How could it not be? Whenever I’m being black and free and saying the things I want to say, that is a form of revolution.”

And while she certainly hopes that people of all walks of life take in the film and consider what it has to say, she’s not shy about the fact that she made this specifically with “the culture” in mind. “Some black art is watered down for white audiences. And the truth is, with white [stuff], you don’t have to do that. Look at Fleabag. Look at Better Things. Look at any white movie that’s been nominated for an Academy Award,” Waithe continued. “But what I felt in movies like Menace II Society, it literally does not care about the white audience at all. Those kinds of films always speak to me in a different way, where I feel seen. Those are the movies that really inspire me.”

Something tells us that, for a new generation of hopeful filmmakers, Queen & Slim just might find itself added to that list.

Queen & Slim is in theaters now.

(E! and Universal Pictures are both part of the NBCUniversal family.)

Source: Read Full Article