A court-appointed independent monitor urged the Trump administration on Wednesday to stop holding migrant children in hotels before summarily expelling them from the U.S. southern border, expressing concerns about a secretive detention system that’s been used to detain at least 660 minors during the coronavirus pandemic.

Since mid-March, U.S. immigration authorities along the southern border have expelled tens of thousands of unauthorized migrants, including an unknown number of children who were encountered without their parents or legal guardians. Instead of deporting them under U.S. immigration law, officials are rapidly expelling most border-crossers without allowing them to seek humanitarian refuge — an unprecedented policy shift that officials say is authorized by a public health statute designed to contain infectious diseases.

Unlike most single adult migrants, who are expelled directly to Mexico by U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP), some unaccompanied minors and families with children processed under the emergency public health directive are held in hotel rooms while officials arrange to expel them through deportation flights. The families and children held in hotel rooms are supervised by personnel from MVM Inc., a private company that contracts with Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE).

Andrea Sheridan Ordin, the independent monitor appointed by a federal court to oversee the government’s compliance with the Flores Settlement Agreement, which governs the care of children in U.S. immigration custody, revealed Wednesday that at least 577 unaccompanied minors were detained in more than 25 hotels between March and July while officials worked to expel them.

Another 83 children have been held in hotels with their families during the same time period, according to an interim report filed by Ordin in the U.S. District Court in Los Angeles.

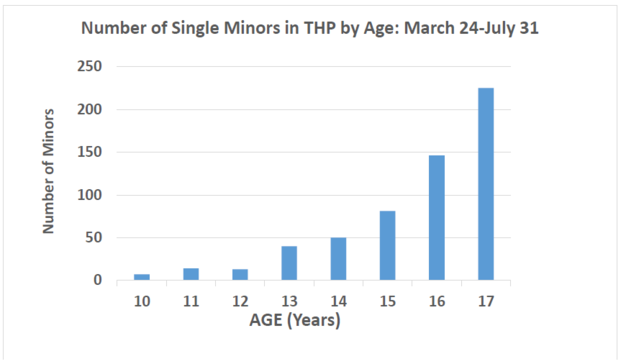

Most of the unaccompanied migrant children held at these border hotels have been teenagers, but some were as young as 10, according to Ordin’s report. In early May, CBS News chronicled the rapid removal of a 10-year-old Honduran boy, the first publicly reported expulsion of an unaccompanied minor under the emergency border policy. Ordin’s report also revealed that the average length of hotel detention for children is approximately five days, but some have been held for nearly a month.

Ordin, a former U.S. attorney in California with decades of legal experience, noted that children held in hotel rooms are provided hot meals, hygiene products, access to medical personnel and other amenities. While she “appreciated” the services, Ordin said the makeshift detention system is “not fully responsive to the safe and sanitary needs of young children.”

“There remains no assurance that the [hotel detention system] can provide adequate custodial care for single minors, who by definition are being moved through the immigration system alone and without familial support or protection,” she wrote in her report.

Ordin urged ICE to cease using hotels to detain children awaiting expulsion — especially those 14 and younger. She said the agency should, at the very least, exempt all minors below the age of 15. “There is a vast body of pediatric and psychological evidence documenting sharp differences in the requisite custodial needs and developmental vulnerabilities of children over this range of ages,” Ordin added.

While Ordin’s recommendation is not binding, advocates believe her findings will bolster their efforts to convince Judge Dolly Gee of the U.S. District Court in Los Angeles to rule that children processed under public health order are entitled to the protections of the Flores settlement, including access to lawyers, placement in safe and sanitary facilities and an obligation that the government pursue the prompt release of minors from detention.

“We hope that the government is ultimately prohibited from flouting its legal obligations through its arbitrary classification of unaccompanied children as ‘single minors’ subject to expulsion under Title 42,” Neha Desai, the director of immigration at the National Center for Youth Law and one of the attorneys in the Flores case, told CBS News, referring to terminology used by the Trump administration.

Justice Department lawyers have argued that these children are not covered under the 1997 Flores consent decree because they are being processed under the public health authorities of an order issued by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

While the use of a public health law to effectively shut down the asylum system to border-crossers is unprecedented in and of itself, the summary expulsions of unaccompanied migrant children is what has alarmed advocates the most.

U.S. immigration and anti-trafficking laws protect unaccompanied migrant children from expedited deportations and require border officials to generally transfer these minors to shelters and other non-restrictive housing facilities overseen by the Office of Refugee Resettlement. Once in the custody of the refugee agency, migrant children can seek asylum or other forms of relief from deportation as they await their release to family members in the U.S.

Ordin’s report is the most detailed account yet of the use of hotel rooms for immigration detention purposes during the pandemic, but it does not include statistics on migrant children expelled by land to Mexico or the total number of minors expelled under the public health order — a figure the Trump administration has repeatedly declined to disclose.

Advocates fear many migrant children processed by U.S. border authorities during the pandemic remain unaccounted for. In April, May, June and July, U.S. officials at the southern border made more than 5,900 apprehensions of unaccompanied children. During that same time span, the Office of Refugee Resettlement reported receiving 330 migrant children from the Department of Homeland Security.

ICE did not immediately respond to a series of questions about the findings and recommendations in Wednesday’s report. The contractor MVM Inc. has said it can’t respond to press inquiries because of its contract with ICE. Citing ongoing litigation, CBP declined to answer several questions, including whether the agency has a policy of not placing unaccompanied children who are 9 or younger in expulsion proceedings.

The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) and other advocacy groups are currently challenging the expulsions of children in federal court. A class-action lawsuit was filed earlier this month after several individual cases were rendered moot because the government removed the named plaintiffs from hotels and greenlighted their transfer to the U.S. refugee agency.

This is a trend documented by lawyers and advocates from groups like Kids in Need of Defense (KIND) and the Young Center for Immigrant Children’s Right. After reaching out to U.S. immigration officials about children held in hotel rooms, the groups said the government has generally abandoned plans to expel those minors.

Ordin also reported Wednesday that at least two children previously held in hotels have been allowed to stay in the U.S. under regular immigration proceedings after testing positive for the coronavirus.

Advocates said it is unclear what factors immigration officials weigh when deciding whether to halt the expulsion of a minor.

“It is really only the threat of litigation that seems to be what causes DHS to say, ‘fine, fine, we’ll re-designate them and transfer them to ORR custody,'” Jennifer Nagda, the policy director at the Young Center for Immigrant Children’s Right, told CBS News. “It doesn’t seem to have anything to do with characteristics of the child, the country of origin, the age, their vulnerabilities or their health — which is allegedly the purpose behind this rule.”

Maria Odom, vice president for legal programs at KIND, said her group has helped halt the expulsions of more than 25 migrant children after finding out about their detention in hotels, usually through family members in the U.S. Odom, however, expressed concern about the minors she and her organization have not been able to locate.

“We’re stripping these kids from their right of seeking legal protection and humanitarian relief to which they are entitled to under the law and I continue to be deeply concerned about the system of housing children in hotels when we have the Office of Refugee Resettlement shelter system designed for the very purpose of housing this vulnerable population,” Odom told CBS News.

Source: Read Full Article