Maria Alves thought the crippling anxiety and worry she said she felt after the birth of her son three years ago were simply “baby blues” that would go away.

When the feelings continued weeks post-delivery and got worse, Alves asked her then-employer, Boston University, for an extension of her maternity leave, which she was granted.

Alves, of Brockton, Massachusetts, was eventually diagnosed with postpartum depression. When she asked Boston University for additional medical leave to give her more time to recover, she was denied the leave and then terminated from her job.

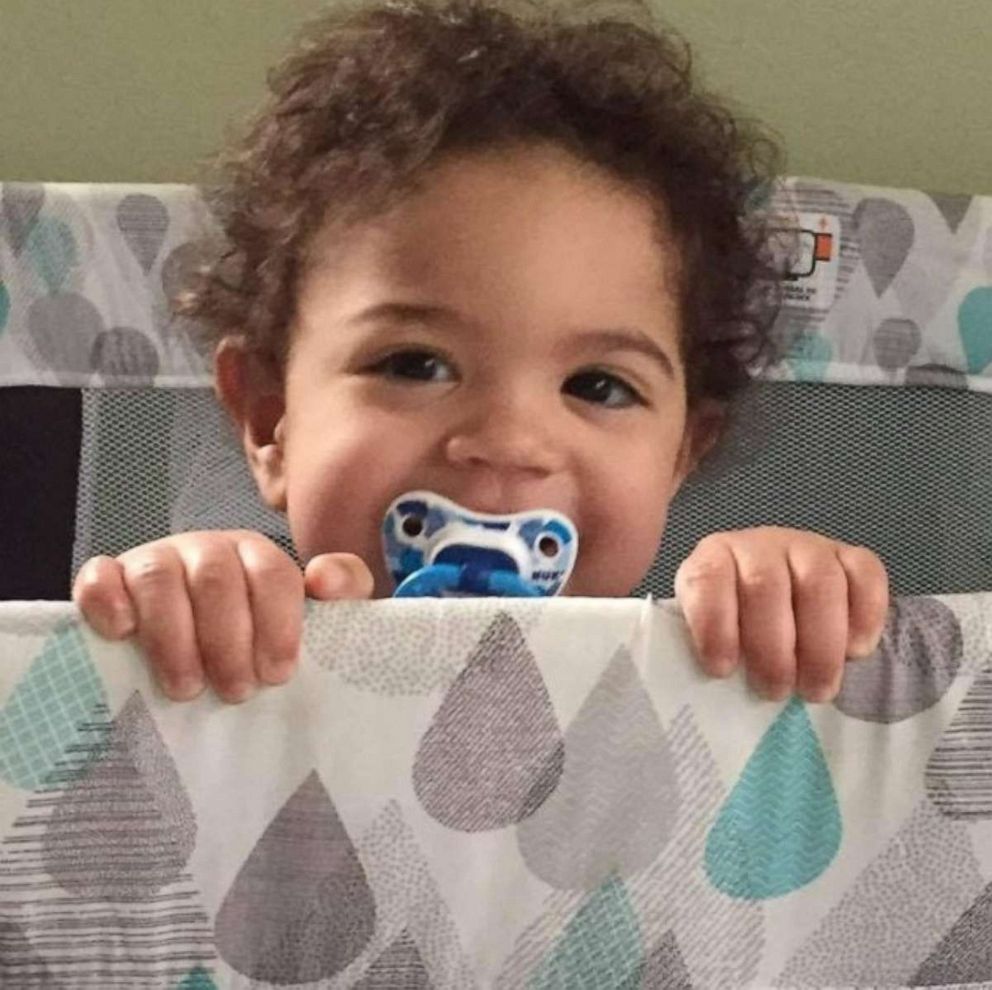

Alves, a single mom, had worked in administrative roles at Boston University for nine years. Her son, Luis, was 4 months old at the time.

“It was a compound effect because you have the postpartum depression and next thing you know I was terminated,” Alves told “Good Morning America.” “Financially it was drastic. I was maxing out credit cards because I had a newborn I had to feed, and clothes and diapers to buy.”

Alves said she isolated herself while suffering from postpartum depression and had only told her sister and a cousin about her struggles. Her cousin happened to work in human resources in another field, and when she learned Alves had been fired, she encouraged her to seek legal help.

Last month, three years after her firing, a jury awarded Alves, now 40, a total of $144,000 in compensatory damages for lost wages and emotional distress at the end of a six-day trial in Suffolk Superior Court.

The 10-person jury ruled that Boston University violated the Massachusetts discrimination laws, specifically disability and medical condition discrimination, based on Alves’ diagnosis of postpartum depression.

“I believe I did the right thing in holding [Boston University] accountable,” Alves said. “Postpartum depression is really real but unfortunately when you have it you don’t want to talk about it and you don’t want to expose yourself for fear of losing your job.”

Postpartum depression is a mood disorder that affects one in nine new mothers in the U.S., according to the U.S. Office on Women’s Health. It is considered a serious mental illness during which feelings of sadness and anxiety may be extreme and may interfere with a woman’s ability to care for herself or her family

“It’s difficult to explain for someone who has never gone through it,” said Alves. “I really didn’t even know what it was. I just knew that my sister had gone through the ‘baby blues’ and I figured it was going to go away for me in a few weeks and it didn’t.”

While many women do not know what to expect with postpartum depression, even more women don’t know what their employee rights are when they are pregnant or suffering from postpartum complications, according to Joan C. Williams, director of the Center for WorkLife Law, a California-based research and advocacy organization.

“Women who are pregnant and women who have postpartum depression often have a qualifying disability under the Americans With Disabilities Act (ADA),” said Williams. “The ADA imposes a whole new set of duties on the employer.”

The ADA, signed into law in 1990, requires employers to work with employees to see if they can create a reasonable accommodation to allow the employee to do the essential parts of the job without creating an undue hardship for the employer, according to Williams.

If, for instance, a woman who is pregnant is a cashier, she could request under the ADA that her employer provide a stool to sit on so she would not have to stand for her entire shift, explained Williams.

“The ADA requires the employer to work with the employee in an interactive process, like, ‘Would this work for you?”” said Williams. “And then the employer would come back with another proposal and say, ‘Well, would this work for you?'”

Alves, who had just been promoted months before her pregnancy, claimed in her lawsuit against Boston University that the university did not work with her to provide a reasonable accommodation. Her attorneys, Matthew Fogelman and Jeff Simons, presented email evidence during the trial and called Alves’ therapist to the stand.

“Their reason [to fire Alves] was that they just couldn’t hold the job any longer, that the department was busy and they needed to fill the position,” said Fogelman. “They tried to argue in the case that there would have been undue hardship on the company but the jury did not find that persuasive.”

Boston University said in a statement to “GMA” in response to the lawsuit, “The University respects the jurors’ verdict and wishes Ms. Alves the best going forward. Thank you.”

Alves will take home around $182,000 after accounting for interest, according to Fogelman.

“I think it’s notable,” he said of the jury’s ruling. “Employers have to be equipped to know how to handle not only maternity leave but other complications, whether it’s a mental condition or a physical condition after birth. Maybe you have to hire a [temporary employee] for another month or maybe you have to borrow someone else from another department or maybe the person can work part-time or from home.”

Williams’ Center for WorkLife Law has established a website, PregnantatWork.org, and a hotline — (415) 703-8276 — as resources for women to know their rights in the workplace.

Williams wants women to know that even beyond paid maternity leave — which only about 35% of women in the U.S. have, according to the Society for Human Resource Management — and the Family Medical Leave Act (FMLA) — which only covers about 50% of workers in the U.S. , according to Williams — they have rights through the ADA.

“That is the big news here,” she said. “What we have found is that OBGYNs often didn’t know that, employers didn’t know that and pregnant women didn’t know that.”

“Not everyone has a cousin in human resources to talk to,” Williams said, referring to Alves.

Alves’ son, Luis, is now 3 and she’s back to work now at a law firm.

Although she has not recovered financially from her termination, Alves said she is on the other side of postpartum depression, no longer isolating herself or living with crippling anxiety.

“Luis is happy. I’m happy. We’re doing good,” she said. “I would hope people with postpartum depression reach out and get help because it is real.”

Source: Read Full Article