In Native American culture, eagles are the ultimate symbol of wisdom, courage, and power. So you'll kindly pardon the interruption when U.S. Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland, who had just hopped on Zoom for this interview from her Washington, D.C., office, is suddenly stopped mid-sentence by her concerned communications director, who had heard a chirping coming from her computer. "Allie, can I pause you for one second? The secretary has a camera that watches eagles, and they're making noises." To which Haaland replies: "The new eagles are getting ready to fledge, so I'm watching every day to see them take their first flight." They are nesting on the campus of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service's National Conservation Training Center in Shepherdstown, West Virginia. "It'll be an exciting day," she says.

Not many executive leaders are sitting in their politically appointed offices living for their Eagle Cam, but then again, Haaland is a bit of an outlier, at least as it pertains to Cabinet members. The former representative from New Mexico became the first Native American Cabinet secretary in U.S. history on March 18, a day when you could practically hear the sound of shattering glass accompanied by a beautiful composition of lilis and drumbeats all across Indian country. Native American communities, environmentalists, and allies all cheered and teared up at the appointment of a leader who understands their needs and is sworn to protect them. Haaland is of the Pueblo of Laguna, and her jurisdiction, previously overseen by non-Native leadership, is significant. It extends to the Bureau of Indian Affairs and the Bureau of Indian Education, and it includes important decisions regarding our nation's public lands and waters. As someone who has been acutely in tune with the notion of caring for Mother Earth from a young age, there has never been a person better suited for this job.

"As a Pueblo woman, I grew up helping my grandfather in his cornfield and watching my grandmother process all that food," Haaland, 60, says. "You see that the earth just keeps giving to us. The water comes through, you irrigate your field, food grows, you sustain yourselves, you have food to share with other people. And with respect to all of our ceremonies or ceremonial activities and so forth, a lot of our songs talk about rain and agriculture and those kinds of things. It's something that has been with us for millennia, and it's just very deeply ingrained in me."

Haaland credits her family's generational work ethic as the reason she's here today. "I'm not always the smartest person in the room. I was able to accomplish a lot just by working hard," she says from her mostly wood office. (I can almost smell the oak through the screen.) "It's about concentrating on the opportunities and the positive things in your life. I know sometimes that's difficult when you're faced with a million challenges every single day, but my grandma taught me to go outside in the morning, greet the sun, and say a prayer to welcome that spirit into your life."

This is a common cultural practice in many tribes, which resonates with me as a Diné, because my mother and grandmother instilled the same lessons. Like many Native women, Haaland's matriarchs and their teachings come through her voice, which is certainly one of deep foundational change. The legacy of resilient ancestors who knew the power of female-led progress has guided her all along. "There was never any question that my grandmother was the boss from the time I was a young girl to the time she passed away," says Haaland. "I feel like she carried that leadership idea with her, even through all of the terrible assimilation years that she encountered going to [a Native American] boarding school, through all of those centuries before her, of [European] colonization – she knew what it meant to be a leader."

Those nurturing forces came in handy when, three days after she graduated college in 1994 at age 34, Haaland became a single mother to Somáh, her only child. "We kind of grew up together," says Haaland, adding that they occasionally subsisted on food stamps to get by. When Somáh was young, Haaland decided to attend law school at the University of New Mexico, so she taught her child how to ride the city bus to get to and from school. She also supplied Somáh with a cellphone, even though Haaland didn't have one until she was 42. During this period, Haaland got her first taste of activism. By banding together with other students who were also balancing school with parenthood, she convinced the dean to start morning classes a half hour later. "So that the parents could drop their kids off at school or get them on the bus or whatever it was before we actually started our first class," she says. "It makes a difference when you are in solidarity with other folks who are facing the same challenges because you can kind of, together, help to make the changes that need to happen."

Following graduation and with an innate desire to help her people, Haaland started running for office. "I ran for lieutenant governor [of New Mexico] in 2014; I ran for Congress in 2018. I just felt like I had an obligation. I wanted to be a leader, and I felt like I could be." And she was: She became one of the first Native American women to be elected to the House of Representatives in its 232-year history along with Kansas representative Sharice Davids (from the Ho-Chunk people). While in office, she overcame the intense polarization in Congress and passed four bills into law with bipartisan and bicameral support, including the Not Invisible Act and the Justice for Native Survivors of Sexual Violence Act, both of which address the crisis of missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls. She was also instrumental in helping to secure $8 billion for tribal nations from the Coronavirus Relief Fund of the CARES Act.

Historically, Native women were the decision-makers in their tribes, but since the onset of colonization, they have, in a sense, become invisible. They are the most underrepresented group in an already marginalized community, which makes Secretary Haaland's position all the more remarkable. "I never really understood what [representation] meant until I became one of the first Indigenous women in Congress," she says. "And representation truly does matter. In the end, that's what it's really about, for people to bring their perspectives to the table. Perspectives that other folks don't necessarily have or haven't thought of."

It's one of the reasons Haaland has welcomed a much more diverse team at the Department of the Interior. This directive is not only important to her but also to her boss, President Joe Biden, whose administration has mandated that a range of people and backgrounds is reflected in his White House. Haaland proudly says that more than 50 percent of her political appointees are people of color and 70 percent are women. "I think it says a lot that we're working to give opportunities to folks who haven't had them in the past," she says. And with an office that is starkly different from the historically white-male-led DOI, they've begun tackling issues of underrepresentation nationally. "In order for our country to care about [marginalized communities], we need to make sure that we're getting their issues out into the open," she explains. "We're bringing those people to the table to have a voice in how they see their future."

One of her first acts as secretary involved establishing a Missing and Murdered Unit to pursue justice for Indigenous peoples affected by these tragedies. "A Native woman could be murdered, and it wouldn't even show up in the newspaper for a week," says Haaland. "Nobody cared about it." For the tribal representatives who have visited her office, the sense of relief is palpable. "'We're so happy,'" she recalls one leader saying. "'We don't have to start with the definition of tribal sovereignty. We can just launch right into our issues.'"

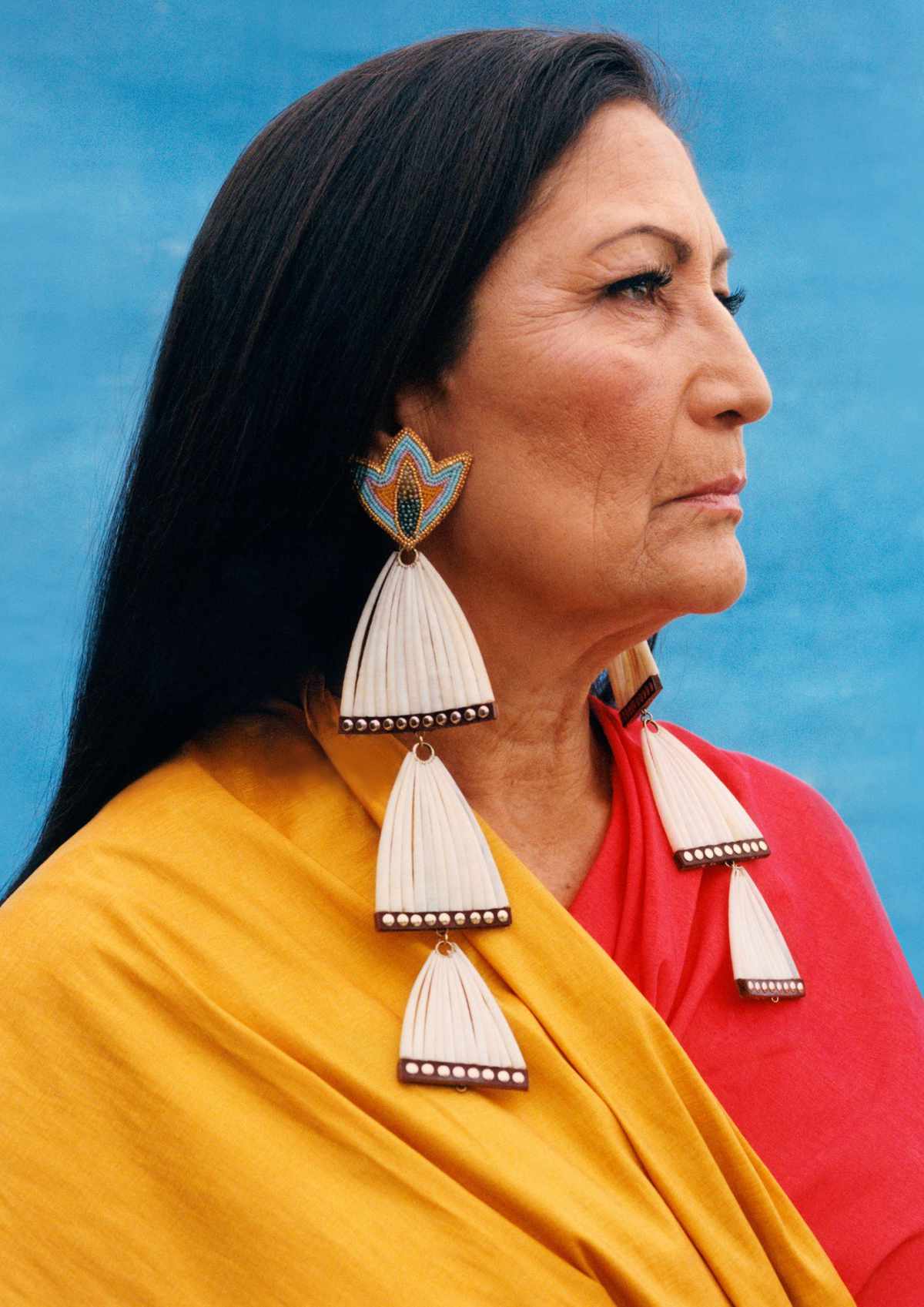

There was perhaps no greater public testament to Haaland's cultural pride than the outfits she chose for her swearing-in ceremonies. A video of her putting on her traditional Laguna moccasins even went viral on social media. "For my congressional swearing-in, I wore my manta and my traditional Pueblo clothes," she explains. "And when I got sworn in as secretary, I wore a ribbon skirt because it's more universal. It speaks for all Native women. The skirt had the corn design, because that's what Pueblo people do: We grow corn. So that was important for me." A few days after Haaland took office, the designer of the skirt, Agnes Woodward of ReeCreeations, posted a photo of the historic moment on Instagram with a long, emotional caption. "Today not just as a ribbon skirt maker but as an Indigenous woman…I feel so seen."

Haaland is looking toward the future with complete clarity and purpose. As a Native woman, she knows the importance of interconnectedness and interdependence, especially as we push toward healing our nation and Mother Earth. Before we sign off, Haaland holds up a photo of a pair of thousand-year-old yucca fiber shoes that she learned about on her first official trip as secretary to Bears Ears National Monument in Utah in April. She is still clearly taken with their existence. "When I saw those shoes, it just made me cry because we've always put so much love, thought, and care into the things we've worn," she says. "That is something foundational in Native designers. They want to honor their ancestors and the things they made or the designs they had. And for me, that comes through incredibly strong. That says everything."

Lead Image: Jamie Okuma skirt, earrings, and boots. Four Winds Gallery Pittsburgh bracelet. Top, stylist's own. Pueblo belt and ring, her own.

Photography by Camila Falquez/Thompson. Styling by Lotte Elisa. Hair and makeup by Alexis Arenas/The Artist Agency. Production by Mike Schoen.

For more stories like this, pick up the August 2021 issue of InStyle, available on newsstands, on Amazon, and for digital download July 16th.

Source: Read Full Article